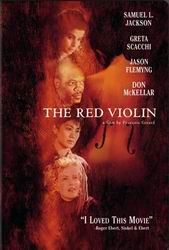

The Red Violin

When most people look at a Stradivarius, they only see a musical instrument. When someone who has a passion for music sees a Stradivarius, they see more. They see its soul, its history, and most of all, its allure. It’s not just musical instrument, but a connection to a time and place that no longer exists.

French-Canadian director Francois Girard and writer Don McKellar understand that connection, and bring it to the screen in one of the year’s most alluring films, “The Red Violin.” Told against a tapestry that spans four centuries, “The Red Violin” is a film that is both inspirational and passionate.

French-Canadian director Francois Girard and writer Don McKellar understand that connection, and bring it to the screen in one of the year’s most alluring films, “The Red Violin.” Told against a tapestry that spans four centuries, “The Red Violin” is a film that is both inspirational and passionate.

Inspirational because it suggests that there are some filmmakers out there who refuse to be held back by Hollywood conventions. Passionate in the sense that everyone in the film shares the same vision, despite the fact that most of the cast never worked together in the same scene.

“The Red Violin” also proves that passion is a universal emotion. Even though the film is episodic, you feel that all of the characters are connected. They share the same goals and dreams, even though they are separated by centuries and continents.

Girard, whose dazzling “32 Short Films About Glenn Gould” showed the world the director’s ability to combine numerous plot threads into a cohesive work, does a splendid job of tying together four different stories. The screenplay by Girard and McKellar (who co-wrote “Glenn Gould” and appears in “Red Violin”) is a virtuoso example of making sense of out chaos.

Most filmmaker’s have a problem telling one story sufficiently, yet Girard juggles four stories here with the finesse of a magician. Remarkably, Girard makes you yearn for more.

The film begins in a modern day auction house in Toronto, where musical expert Charles Morritz has been summoned to authenticate a shipment of rare instruments from the Peoples Republic of China. Along the way, Morritz discovers a musical instrument that he believes to be the infamous “Red Violin.”

As Morritz begins the process of proving his theory, the filmmakers flash back to 17th Century Italy, where the violin was born out of love. It was crafted by Nicolo Bussotti (Carlo Cecchi) as a gift for his unborn son, who will grow up to be a master musician. The dream is never realized when Nicolo’s wife, Anna (Irene Grazioli) dies during childbirth.

Through the centuries, the violin finds it way to an orphanage outside of Vienna, then to the English residence of an English concert violinist, and finally to China during the cultural revolution of the 1960’s. Even though this cinematic device has been used before, (“La Ronde” and “20 Bucks” immediately come to mind), Girard and McKellar have seamlessly tied together these diverse events with two narratives.

One involves Morritz, a man who makes a comfortable living but in no way could afford to own the infamous “Red Violin.” The other involves Anna’s fortune-teller, whose advice as she overturns each of five cards sets the tone for the rest of the film.

I especially appreciated the way the filmmaker’s never underestimated their audience. They keep their cards close to their vest, never telegraphing or giving away too much. There are many surprises in the film, none of which are spoiled by the filmmaker’s. English is only spoken when appropriate. Otherwise, characters speak in their native tongues.

The international cast is marvelous. There isn’t a bad performance in the film, while some actually soar above the rest. Jackson is outstanding as a man who knows his pocketbook will never match his passion. The auction sequence that begins and ends the film is actually quite riveting, as the writer’s only reveal little pieces at a time.

Carlo Cecchi and Irene Grazioli shine as the master craftsman who makes the violin and his concerned wife. Their relationship feels real and full of hope, even though they live in particularly dark time. Jason Flemyng is just amazing as the British concert violinist who gets inspiration from both the violin and his mistress, a seductive Greta Scacchi.

Christoph Koncz stands out as the sickly child prodigy who wants to be famous, while Sylvia Chang finds depth in her role as a Chinese revolutionary who understands the difference between Western corruption and art.

The writers hardly give us enough time to enjoy the benefits of each segment, leaving us wanting more. Even though some details are sketchy at best, the passion the players and filmmakers approach the material with more than compensates .

Technically, “The Red Violin” is a masterpiece of visual images. The production design, which spans 300 years and several continents, is absolutely smashing. The production team manages to take us back in time with believable results. The heart of the film is its music, and like all those that came before it (“Hilary & Jackie,” “The Competition”), it beats with authority. The violin solos are so powerful you can’t help but be swept up into them.

While it’s not for everyone, “The Red Violin” remains one of the best film os 1999 (even though it was released last year abroad and in Canada). It contains the sort of spirit and individuality that makes going to the movies more than just sport. It has something important to say and does so eloquently.

Samuel L. Jackson, Carlo Cecchi, Irene Grazioli, Jason Flemyng, Greta Scacchi, Sylvia Chang, Colm Feore, Don McKellar, Anita Laurenzi, Christoph Koncz, Jean-Luc Bideau, Liu Zifeng in a film directed by Francois Girard. Not rated. 126 Minutes.

LARSEN RATING: $8